In “What if we can influence behavior in the real world based on experiences in the virtual world?” So begins Dr. Barbara O. Rothbaum’s 2016 TEDx Talk on using virtual reality to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), phobias, and anxiety. In the same year, the first commercial version of Oculus Rift was launched alongside the HTC Vive and PSVR, and the Samsung Gear VR became a popular smartphone compatible alternative to more complex setups, prompting new outlets to position 2016 as the year virtual reality became a reality.

In the years to follow, virtual reality has waxed and waned in popularity. Everyone from filmmakers and gamers to scientists and researchers have weighed buy-in costs for virtual reality with outcomes, pondered the role of VR in cinematic storytelling, and questioned how this immersive media can affect change.

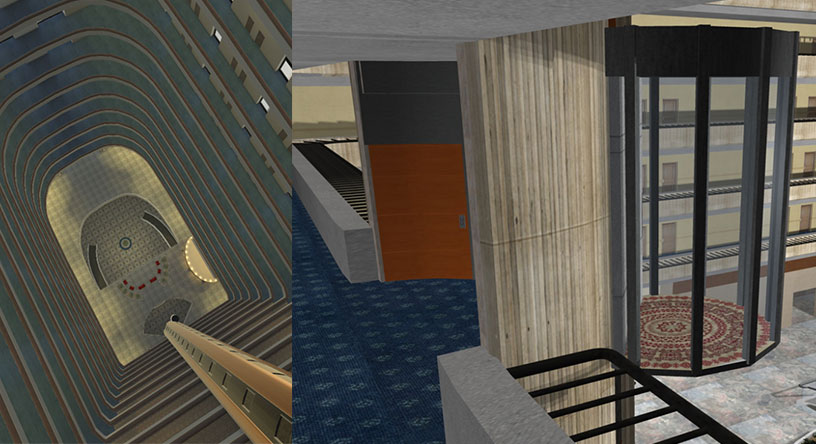

When it comes to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), VR can be used for treatment of various anxiety disorders—a field Dr. Rothbaum has been researching since 1993. In her tenure, Rothbaum has used virtual environments of warzones to treat PTSD, virtual bars to treat addiction, and simulations of planes taking off and elevator rides to treat phobias of flying and heights. “In general, what we do with cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders, including PTSD, is exposure therapy,” Rothbaum said. “What that is, is helping people to confront what they’re scared of in a therapeutic manner, so that something changes.” Prior to the use of virtual environments, exposure therapy was done using imagination or in vivo (in real life). In vivo can include sessions where a therapist accompanies their patient on a plane ride to confront a fear of flying or rides an elevator floor by floor until the patient is able to ride an elevator to the top of a skyscraper without anxiety. This process can be costly and complex.

Virtual reality, however, provides a simulated reality for exposure therapy that is not only cheaper and more accessible, but it provides a new level of control for the therapist. In VR, the therapist can control the turbulence of a simulated plane or recreate a warzone—all without leaving the office.

When comparing exposure therapy to treat the fear of flying in VR alongside traditional exposure therapy, Rothbaum discovered that VR was just as effective, noting that 90% of people in both VR and in vivo groups flew on their own after treatment.

On the heels of this discovery, Rothbaum cofounded Virtually Better in 1996, an Emory and Georgia Tech startup that creates virtual environments for the use of treating anxiety disorders.

Rothbaum noted that the success of VR is much more than a headset and visuals. “For real virtual reality, people feel a sense of presence in that environment. For example, I could show you a picture of the room I’m in and you’d get a sense, I could take the video of the room I’m in, you get a little bit better sense, but you wouldn’t feel present in it. If I had this room rendered in virtual reality that you would feel present, you could go under the desk,” Rothbaum explained. “A lot of times when people show videos in a head-mounted display, they call it virtual reality, and I don’t call that virtual reality.”

When treating veterans with PTSD, Rothbaum explained that sound and kinesthetics aids in creating an effective virtual environment. “If they’re in the Humvee, you can feel the engines on, you can feel the explosions, you can feel the vibration of the helicopter rotors, and it’s harder to avoid because it’s so evocative. We can recreate situations that we couldn’t do in reality.”

VR in CBT also relies on the patient’s imagination, as Dr. Margo Adams Larsen, Director of Research and Training at Virtually Better told Oz, “It’s often really surprising to folks that our VR does not look like the highest quality gaming VR that’s out there, and it’s not because we can’t do that. It’s because what we know in the research is if we do that, we take away from the individualized ability of the intervention. Meaning the less detail there is, the more suggestion there is, the more the patient is able to map their imagination of, either what they’re remembering or what their fear is, into that environment.”